This Dr. Axe content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure factually accurate information.

With strict editorial sourcing guidelines, we only link to academic research institutions, reputable media sites and, when research is available, medically peer-reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses (1, 2, etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

The information in our articles is NOT intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified health care professional and is not intended as medical advice.

This article is based on scientific evidence, written by experts and fact checked by our trained editorial staff. Note that the numbers in parentheses (1, 2, etc.) are clickable links to medically peer-reviewed studies.

Our team includes licensed nutritionists and dietitians, certified health education specialists, as well as certified strength and conditioning specialists, personal trainers and corrective exercise specialists. Our team aims to be not only thorough with its research, but also objective and unbiased.

The information in our articles is NOT intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified health care professional and is not intended as medical advice.

Atrazine: the Most Common Toxic Contaminant in Our Water

September 26, 2016

Almost all of us go out of the way to avoid harmful toxins and poisons: We wouldn’t leave bleach near a toddler, for instance, and most of know about the dangers of Monsanto Roundup. But what if the toxin is something that’s quite hard to escape … and we’re consuming it unwittingly, without knowing exactly what will happen to us?

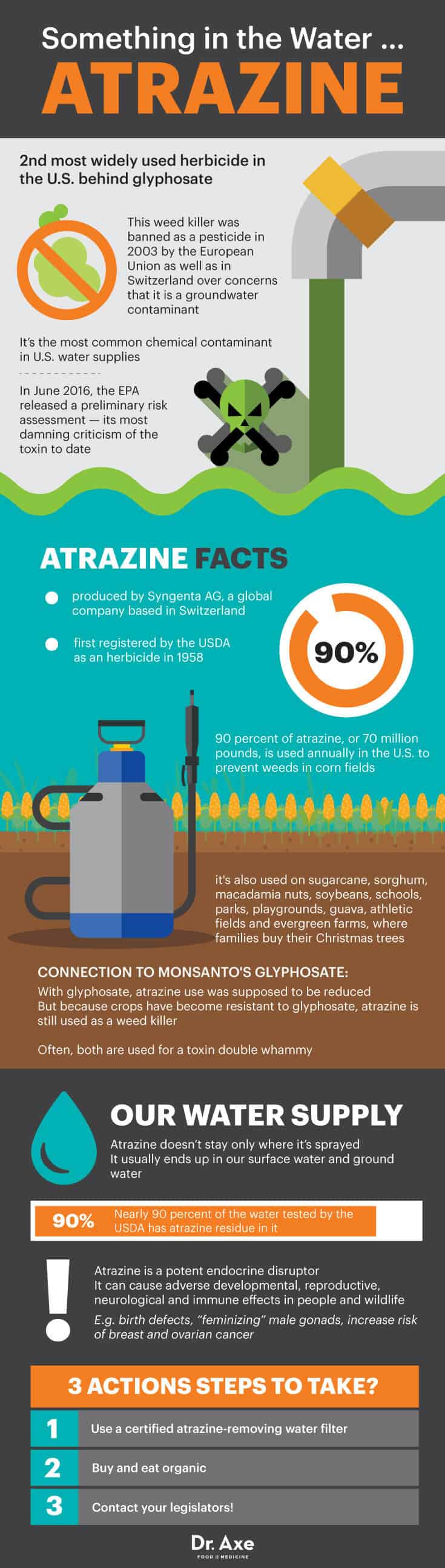

Say hello to atrazine, the second-most widely used herbicide in the U.S. behind glyphosate (the active ingredient in Roundup) and likely just as dangerous, most infamously as an endocrine disruptor. While other countries have banned the herbicide, atrazine is still used in American crops — and often winds up in our water supply. In fact, it’s the most common chemical contaminant in U.S. water supplies.

In June 2016, the Environmental Protection Agency released a preliminary risk assessment, its most damning criticism of the toxin to date. But with a public comments date that’s been extended from the initial 60-day period and the federal wheels of bureaucracy moving ever so slowly, it’s up to each of us to take steps to reduce our exposure to atrazine and avoid its toxic effects.

So what exactly is atrazine? And how is it that although it’s quite prevalent in America and contributes to our tap water toxicity, most of us haven’t ever heard of it? It’s time to delve into the dirty nitty gritty of atrazine.

What Is Atrazine? A Look at the Toxin and Its History

Atrazine is an herbicide produced by Syngenta AG, a global company based in Switzerland. In the U.S., the product is used mainly to kill weeds. It was first registered by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) as an herbicide in 1958.

While 90 percent of atrazine, or 70 million pounds, is used annually in America is to prevent weeds in corn fields, atrazine is also used on sugarcane, sorghum, macadamia nuts, soybeans, schools, parks, playgrounds, guava, athletic fields and evergreen farms, where families buy their Christmas trees. (1, 2) In fact, 65 percent of sorghum and sugarcane fields are treated with atrazine. It’s also used in other products for farming and landscaping purposes, about 200 in total.

When Monsanto’s glyphosate came onto the scene, the idea was that atrazine use would be reduced. But because crops have become resistant to glyphosate, atrazine is still used as a weed killer, often in conjunction with glyphosate for a toxin double-whammy.

Having a toxin sprayed on corn and crops is bad enough but, like most pesticides, atrazine doesn’t stay only where it’s sprayed. It usually ends up in our surface water and ground water, which means it’s in our nation’s drinking water supply. (3, 4) Nearly 90 percent of the water tested by the USDA has atrazine residue in it. (5)

So if it atrazine has been approved for use, why is it so harmful — and why is the EPA finally taking notice?

Toxic Effects of Atrazine

Syngenta, the company behind atrazine, would have you believe that the herbicide is perfectly safe. According to them, “Atrazine is effective, safe, and integral to agriculture’s success in the United States and worldwide.” (6) But that couldn’t be further from the truth.

Atrazine Is an Endocrine Disruptor

One of atrazine’s scariest effects is that it is an endocrine disruptor. These are chemicals foreign to the human body that, after a certain level of exposure, disrupt our endocrine — also known as hormonal — systems. Endocrine disruptions can cause adverse developmental, reproductive, neurological and immune effects in people and wildlife.

This occurs because the endocrine system includes hormone-secreting glands and is in charge of regulating blood sugar, our reproductive systems, metabolism, brain function and the nervous system. Our bodies are kept in check with a delicate balance. When one hormone goes out of whack, it can have serious ripple effects throughout the body. (7)

When it comes to atrazine, its endocrine disruption abilities are frightening. A 2011 study published in The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology summarized a huge swath of research on atrazine, dating back to 1997. The study alone features 22 authors from around the globe. (8)

The study confirmed what researchers have been saying for years: atrazine “demasculinizes” and “feminizes” vertebrate male gonads. In other words, atrazine is a “decrease in male gonadal characteristics,” because the herbicide shrinks testicles and reduces sperm counts. By “feminizing” male gonads, atrazine can lead to the growth of ovaries in males.

Frogs turning from males into females means they can now mate with male frogs. But since the female frogs are still genetically male, their offspring are all male. This leads to a major skewing of the sex ratios in a population, which leads to a decrease or even an elimination of the population. (9)

And while much of the media attention has been on how male frogs can turn into females, what this comprehensive study found is that the effects “do not occur merely across populations, species or even genera or orders, but across vertebrate classes.” That means they occur across amphibian, fish, mammal and reptile species.

The researchers believe these scary changes occur because atrazine reduces production of male hormones, while increasing the effect of estrogen, a female hormone. The atrazine levels that frogs which change sex are exposed to is less than what’s legally allowed in our water — it occurs at levels as low as 0.1 parts per billion, or PPB. In comparison, the EPA allows atrazine at levels 30 times higher than this in our drinking water — 3 ppb.

Women are probably familiar with hearing about estrogen; Raised levels of the hormone increase risk of breast and ovarian cancer. So it should come as no surprise that high levels of atrazine in water or long-term exposure to atrazine have been found to do the same. (10, 11) While a direct link hasn’t been found, the research is certainly concerning.

Water Supply and the Environment

While we grapple with how to deal with atrazine in America, it’s worth noting that our trans-Atlantic neighbors no longer face these same issues. That’s because during the herbicide’s periodic review in October 2003, while the EPA approved it for continued use once again, the European Union banned it because of the ubiquitous and unpreventable water contamination. (12)

Atrazine’s infiltration in our water supply is indeed serious. Tests done by the EPA itself have found that water supplies often exceed the 3 ppb they deem safe in the supply. (13) It’s especially troubling in the Midwest and Southwest, where atrazine is most widely used.

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) analyzed 20 Midwestern watersheds between 2007–2008. All 20 showed detectable levels of atrazine. Sixteen had an average concentration over 1 ppb, which is the amount that’s been shown to do damage to wildlife and plants (and yet somehow the legal limit is 3 ppb). Eighteen of the 20 watersheds were intermittently contaminated with a sample above 20 ppb; nine had concentrations above 50 ppb; three had maximums exceeding 100 ppb. (14)

But I thought the legal limit is 3 pbb, you ask. The federal government requires monitoring only four times a year, while this study monitored the water weekly and bi-weekly. This lax federal system means that residents drinking water aren’t alert to high spikes in atrazine, particularly during summertime, when contamination seems to be highest.

The same comprehensive NRDC report also analyzed water from 153 water stations throughout the U.S. between 2005 and 2008. The results were just as troubling. Eighty percent of untreated and ready-for-consumption water contained detectable levels of atrazine. Two-thirds had peak maximum concentrations of atrazine that exceeded 3 ppb in the finished drinking water.

Residents usually don’t know that atrazine is in their water supply, to give them the option of using filtered water. And removing it is expensive, as communities have to install expensive water treatment systems. In fact, in some places where local officials are concerned about atrazine levels, water systems have actually sued atrazine manufacturers to make them pay for the costs of removing the herbicide from the drinking water. (15)

This is scary for anyone, but especially for pregnant women. There are several birth defects that have been linked to surface water atrazine. (16, 17)

One study found that rare birth defect of the nasal cavity, choanal atresia, was linked to atrazine. The condition impairs a baby’s ability to breathe, and it’s thought that chemicals which affect the mom’s endocrine system are to blame. The study found that babies born to mothers in Texas counties known to have high atrazine use had almost double an increase in risk. (18)

What’s Going on with the EPA?

So where is the EPA in all of this? Well, it seems that after years of scientists and the public urging the EPA to open its eyes, we are finally on a (slow) path to change.

In April 2016, the EPA released its risk assessment for atrazine, its first since 2003. (19) The EPA is required to evaluate pesticides approved for use at least once every 15 years. In those 12 years, enough research has come to light that it seems even the EPA couldn’t turn a blind eye.

The report found that in areas where atrazine is most used, like the corn belt, atrazine in the environment is measured at rates past set levels of concern by “as much as 22, 198 and 62 times for birds, mammals and fish, respectively.”

The assessment also cited studies by Tyrone Hayes, a biologist who was the first to uncover atrazine’s effects on sex changes in frogs. Initially hired by Syngenta in the late ‘80s to prove that atrazine wasn’t harmful, Hayes ended up uncovering just the opposite.

It is expected that in late 2016, the EPA will release a separate report detailing atrazine’s impact on human health. Together with the current risk assessment, these new reports could determine how the EPA decides to re-authorize atrazine — if it does at all.

Alternatives to Atrazine?

Eliminating atrazine altogether, the way the EU did, would be ideal. Researchers have found that, opposite what Syngenta claims, the effect on farmers would be minimal. In fact, it would lead to an increase in corn prices of 8 percent and raise consumer prices by only pennies — a gas prices would rise by no more than $0.03 per gallon, for instance, while corn growers would actually see an increase in revenue. And the crop yields? Well, those would decrease by just 4 percent. (20)

There are other methods we can take to reduce reliance on atrazine. Crop rotation, winter cover crops, alternating rows of different crops and mechanical weed control methods can all help reduce weed growth naturally.

And as they say, necessity is the mother of all invention — the federal government could spur innovation by funding creative techniques to stop weeds in their tracks without using harmful chemicals.

Finally, it should be noted that if almost an entire continent can get by without atrazine, surely the most powerful country in the world can, too.

Action Plan to Avoid Atrazine Exposure

Atrazine is scary stuff. So what’s the best way to avoid exposure and protect yourself and your family?

1. Use a water filter

Bottled water is expensive and harmful for the environment, but you can purchase an inexpensive water filter at local retailers. Just check the labeling to ensure it’s certified to remove atrazine.

While this won’t limit all exposure to atrazine in water, this small step can make a big difference.

2. Buy organic

When you purchase organic crops, you can be sure that they haven’t been treated with dangerous chemicals. Although traces might remain — those chemicals do travel far — it’s nothing like buying the regular stuff.

I appreciate that organic food is more expensive, but you are investing in your health. You can also opt for organic frozen fruits and veggies that won’t spoil quickly.

Shop at the farmer’s market to buy produce that’s in season and usually less expensive. At a minimum, make sure any corn you purchase is organic, as nearly all non-organic corn in the U.S. is grown in atrazine-sprayed fields.

3. Contact your legislators

Tell them to advocate for the health of the communities they represent. While the EPA is independent, it does have to answer to the public and Congress. In your local community, ask for more frequent water testing.

Final Thoughts

Being told that you’re constantly exposed to a dangerous chemical — and you can’t do much about it — is terrifying. But if enough of us are aware of the problem and demand action from our lawmakers, our farmers and the agencies designed to protect us, change can happen.