This Dr. Axe content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure factually accurate information.

With strict editorial sourcing guidelines, we only link to academic research institutions, reputable media sites and, when research is available, medically peer-reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses (1, 2, etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

The information in our articles is NOT intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified health care professional and is not intended as medical advice.

This article is based on scientific evidence, written by experts and fact checked by our trained editorial staff. Note that the numbers in parentheses (1, 2, etc.) are clickable links to medically peer-reviewed studies.

Our team includes licensed nutritionists and dietitians, certified health education specialists, as well as certified strength and conditioning specialists, personal trainers and corrective exercise specialists. Our team aims to be not only thorough with its research, but also objective and unbiased.

The information in our articles is NOT intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified health care professional and is not intended as medical advice.

Stop Using Bug Zappers Immediately

May 25, 2018

Bug zappers may seem like a tempting solution if you find yourself Googling home remedies for mosquito bites during peak skeeter season. But there are a number of compelling reasons to avoid going the bug electrocution route.

Now, to be clear, avoiding Zika virus and ailments like West Nile Virus should be on your radar. I’m just here to tell you that I would not turn to bug zappers for adequate protection. There are better (and way less gross) ways. (More on that later).

The History of Bug Zappers

The idea of electrofying insects first became a thing in 1911 when Popular Mechanics magazine introduced the concept. Still, most thought it was too expensive to undertake at the time. Fast forward to 1932, when the first patented electric fly zapper was recorded by U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Just two years later, a University of California professor of parasitology introduced the bug zapper that would be the basis for all future zappers. (1)

Bug zappers are also known as:

- Electrical discharge insect control systems

- Electric insect killers

- Insect electrocutor traps

The Problem with Bug Zappers

While it seems appealing to invite pests into your yard and then fry them, science tells us that may not be such a great idea. Here are some of the major flaws associated with bug zappers that you should know about.

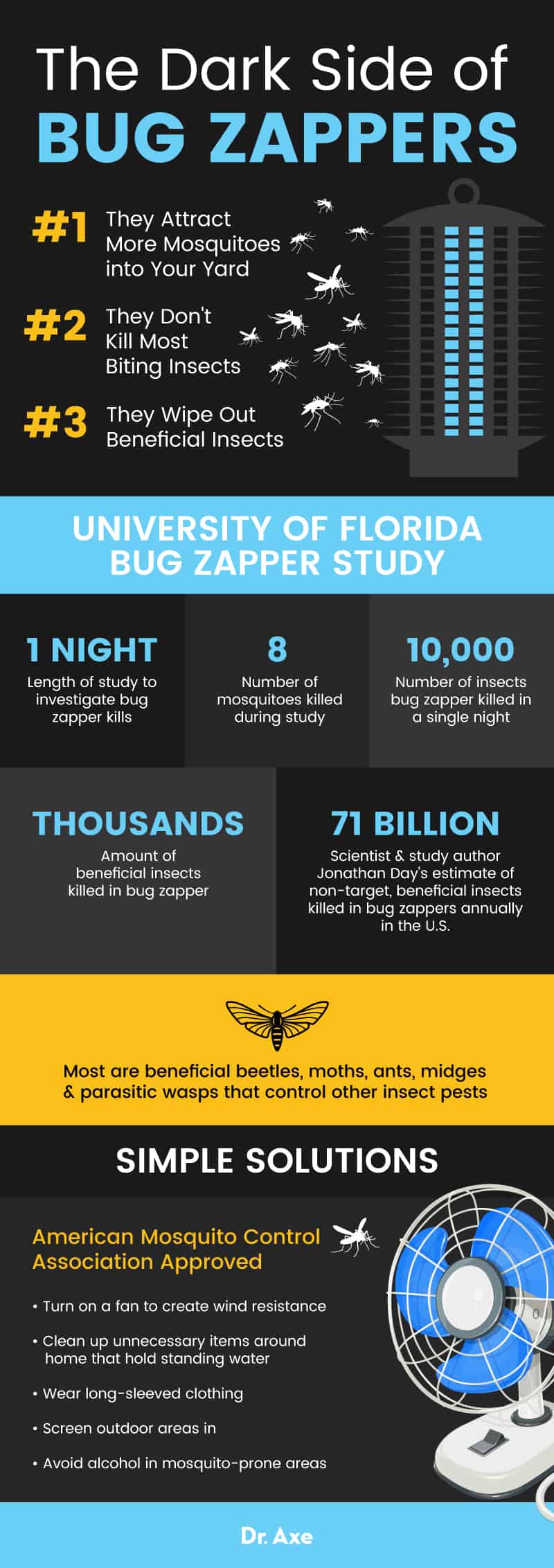

They don’t work. Bug zappers kill tons of beneficial insects while missing most of the biting insects that pest us, explains a University of Florida pest control expert (2, 3)

“[Bug zappers] are a total waste of money. Bug zappers will not control mosquitoes or other biting insects such as horseflies, dogflies or deerflies,” says Jonathan Day, PhD, associate professor of entomology in University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

“They simply do not work as advertised. In fact, bug zappers actually make things worse by attracting more mosquitoes into your yard, and they end up killing thousands of beneficial insects that don’t bother people.”

Be wary of zappers that market carbon dioxide as an attractant, too. Mosquitoes are drawn to carbon dioxide but studies show they prefer the natural form that is emitted from humans versus artificial sources.

Another reason to avoid zappers? Bug viruses and bacteria travel long distances upon electrocution. A nicer way of saying this is microscopic bug guts is sprayed onto people sitting around the bug zapper … and into nearby food. (4, 5)

The best ways to avoid mosquitoes in your favorite outdoor areas are to:

- Screen in the area, if possible

- Use a fan; it disperses CO2 and creates wind resistance to keep mosquitoes away

- Avoid drinking alcohol if you’re in a mosquito-prone area (6)