This Dr. Axe content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure factually accurate information.

With strict editorial sourcing guidelines, we only link to academic research institutions, reputable media sites and, when research is available, medically peer-reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses (1, 2, etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

The information in our articles is NOT intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified health care professional and is not intended as medical advice.

This article is based on scientific evidence, written by experts and fact checked by our trained editorial staff. Note that the numbers in parentheses (1, 2, etc.) are clickable links to medically peer-reviewed studies.

Our team includes licensed nutritionists and dietitians, certified health education specialists, as well as certified strength and conditioning specialists, personal trainers and corrective exercise specialists. Our team aims to be not only thorough with its research, but also objective and unbiased.

The information in our articles is NOT intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified health care professional and is not intended as medical advice.

The Human Microbiome: How It Works + a Diet for Gut Health

January 13, 2023

Most people think of bacteria within the body as a cause of getting sick or developing certain diseases, but did you know that at all times there are actually billions of beneficial bacteria present within all of us? In fact, bacteria make up the microbiome, an integral internal ecosystem that benefits gut health and the immune system.

The scientific community has really come to embrace the important role that bacteria have in fostering a strong immune system and keeping us healthy. Not only are all bacteria not detrimental to our health, but some are actually crucial for boosting immunity, as well as keeping our digestive systems running smoothly, our hormone levels balanced and our brains working properly.

What is the microbiome, why is it so important and how can we protect it? Let’s find out.

What Is the Human Microbiome?

Each of us has an internal complex ecosystem of bacteria located within our bodies that we call the microbiome. The microbiome is defined as a community of microbes. The vast majority of the bacterial species that make up our microbiome live in our digestive systems.

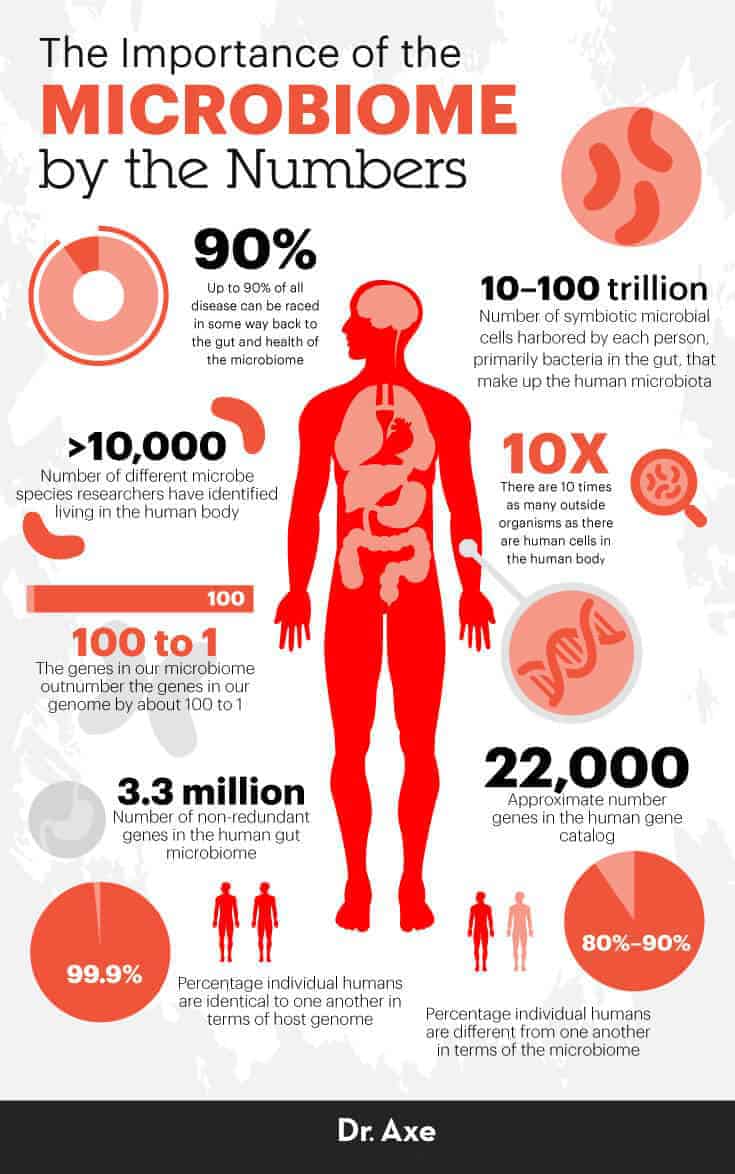

According to the Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry at the University of Colorado, “The human microbiota consists of the 10–100 trillion symbiotic microbial cells harbored by each person, primarily bacteria in the gut. The human ‘microbiome’ consists of the genes these cells harbor.”

Our individual microbiomes are sometimes called our “genetic footprints” since they help determine our unique DNA, hereditary factors, predisposition to diseases, body type or body “set point weight,” and much more. The bacteria that make up our microbiomes can be found everywhere, even outside our own bodies, on nearly every surface we touch and every part of the environment we come into contact with.

The microbiome can be confusing because it’s different than other organs in that it’s not just in one location and is not very large in size — plus it has very far-reaching roles that are tied to so many different bodily functions. Even the word “microbiome” tells you a lot about how it works and the importance of its roles, since “micro” means small and “biome” means a habitat of living things.

It’s been said by some researchers that up to 90 percent of all diseases can be traced in some way back to the gut and health of the microbiome. Believe it or not, your microbiome is home to trillions of microbes, diverse organisms that help govern nearly every function of the human body in some way.

The importance of the gut microbiome cannot be overstated: Poor gut health can contribute to leaky gut syndrome and autoimmune diseases, along with disorders like arthritis, dementia, heart disease and cancer. Our health, fertility and longevity are also highly reliant on the balance of critters living within our guts.

Throughout our lives, we help shape our own microbiomes — plus they adapt to changes in our environment. For example, the foods you eat, how you sleep, the amount of bacteria you’re exposed to on a daily basis and the level of stress you live with all help establish the state of your microbiota.

Related: What Is the Oral Microbiome? How to Balance It to Improve Overall Health

How It Works

Would you believe that within the human body there are about 10 times as many outside organisms as there are human cells? Microbes inhabit both the inside and outside of our bodies, especially residing in the gut, digestive tract, genitals, mouth and nose areas.

What determines if someone’s microbiome is in good shape or not? It comes down to the balance of “bad bacteria” versus “good bacteria.”

Essentially, we need a higher ratio of gut-friendly “bugs” to outnumber those that are harmful in order to stay resilient and symptom-free. Unfortunately — due to factors like a poor diet, high amounts of stress and environmental toxin exposure — most people’s microbiomes are home to many billions of potentially dangerous bacteria, fungus, yeast and pathogens. When we carry around more pathogenic bacteria than we should, and also lack the diversity of protective bacteria we need, the microbiota suffers.

The human microbiome is home to more than just bacteria. It also houses various human cells, viral strains, yeasts and fungi — but bacteria seem to be the most important when it comes to controlling immune function and inflammation. To date, researchers have identified more than 10,000 different species of microbes living in the human body, and each one has its own set of DNA and specific functions.

There’s still lots to learn about how each strain of bacteria affects various parts of the body and how each can either defend us from or contribute to conditions like obesity, autoimmune disorders, cognitive decline and inflammation.

Microbiome Diet

Your diet plays a big part in establishing gut health and supporting your microbiome’s good bacteria. Research over the past several decades has revealed evidence that there’s an inextricable link between a person’s microbiota, digestion, body weight and metabolism.

In an analysis of humans and 59 additional mammalian species, microbiome environments were shown to differ dramatically depending on the specie’s diet.

The flip side is also true: Your gut health can impact how your body extracts nutrients from your diet and stores fat. Gut microbiota seem to play an important role in obesity, and changes in bacterial strains in the gut have been shown to lead to significant changes in health and body weight after only a few days.

For example, when lean germ-free mice receive a transplant of gut microbiota from conventional/fat mice, they acquire more body fat quickly without even increasing food intake, because their gut bugs influence hormone production (like insulin), nutrient extraction and fat (adipose tissue) storage.

Now that you can see why it’s critical to lower inflammation and support gut health, lets’s take a look at how you can go about this.

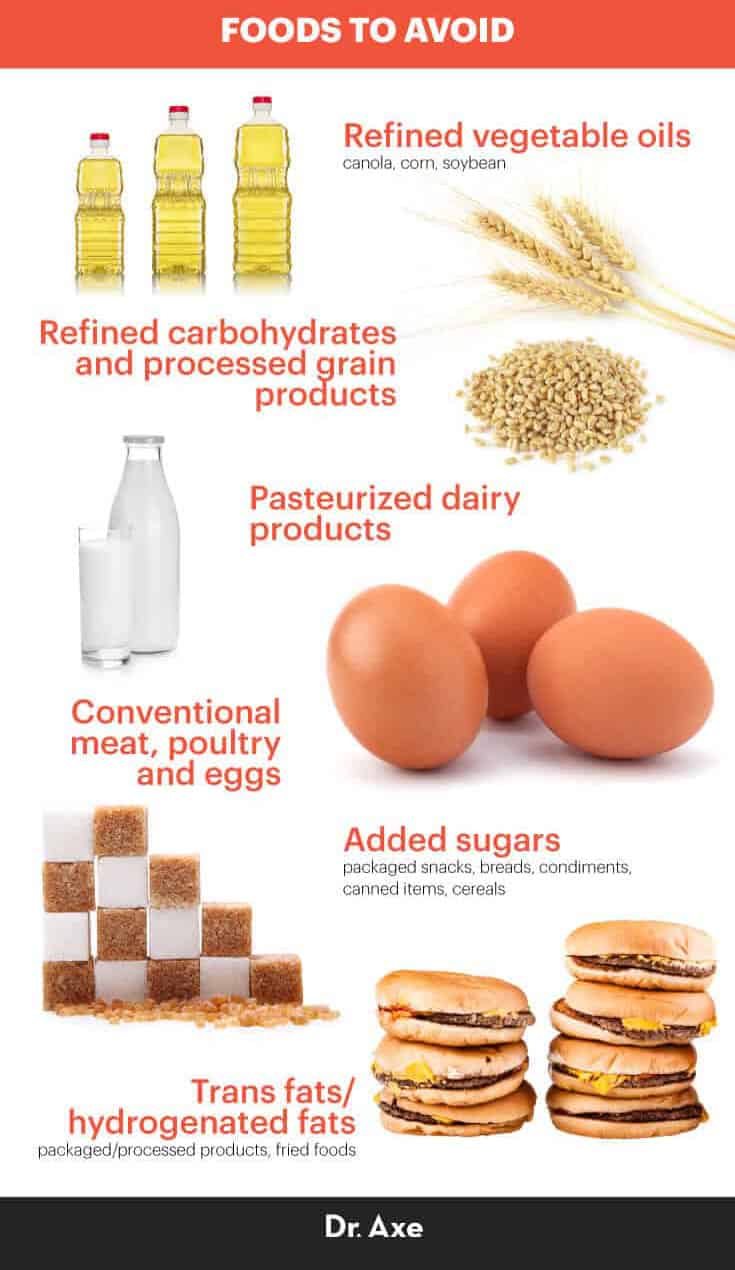

Foods that promote inflammation include:

- Refined vegetable oils (like canola, corn and soybean oils, which are high in pro-inflammatory omega-6 fatty acids)

- Pasteurized dairy products (common allergens)

- Refined carbohydrates and processed grain products

- Conventional meat, poultry and eggs (high in omega-6s due to feeding the animals corn and cheap ingredients that negatively affect their microbiomes)

- Added sugars (found in the majority of packaged snacks, breads, condiments, canned items, cereals, etc.)

- Trans fats/hydrogenated fats (used in packaged/processed products and often to fry foods)

On the other hand, many natural foods can lower inflammation and help increase good bacteria in the gut. High-antioxidant foods help reduce gut damage caused by oxidative stress and turn down an overactive immune system while safeguarding healthy cells.

Anti-inflammatory foods that should be the base of your diet include:

- Fresh vegetables (all kinds): Loaded with phytonutrients that are shown to lower cholesterol, triglycerides, and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Aim for variety and a minimum of four to five servings per day. Some of the best include beets, carrots, cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower and kale), dark leafy greens (collard greens, kale, spinach), onions, peas, salad greens, sea vegetables and squashes.

- Whole pieces of fruit (not juice): Fruit contains various antioxidants like resveratrol and flavonoids, which are tied to cancer prevention and brain health. Three to four servings per day are good for most people, especially apples, blackberries, blueberries, cherries, nectarines, oranges, pears, pink grapefruit, plums, pomegranates, red grapefruit or strawberries.

- Herbs, spices and teas: Turmeric, ginger, basil, oregano, thyme, etc., plus green tea and organic coffee in moderation.

- Probiotics: Probiotic foods contain “good bacteria” that populate your gut and fight off bad bacterial strains. Try to include probiotic foods like yogurt, kombucha, kvass, kefir or cultured veggies in your diet daily.

- Wild-caught fish, cage-free eggs and grass-fed/pasture-raised meat: Higher in omega-3 fatty acids than conventional farm-raised foods and great sources of protein, healthy fats, and essential nutrients like zinc, selenium and B vitamins.

- Healthy fats: Grass-fed butter, coconut oil, extra virgin olive oil, nuts/seeds.

- Ancient grains and legumes/beans: Best when sprouted and 100 percent unrefined/whole. Two to three servings per day or less are best, especially Anasazi beans, adzuki beans, black beans, black-eyed peas, chickpeas, lentils, black rice, amaranth, buckwheat, quinoa.

- Red wine and dark chocolate/cocoa in moderation: Several times per week or a small amount daily.

How to Support It

1. Avoid Antibiotics as Much as Possible

Antibiotics have been commonly prescribed for over 80 years now, but the problem is that they eliminate good bacteria in addition to cleaning the body of dangerous “germs,” which means they can lower immune function and raise the risk for infections, allergies and diseases. While antibiotics can save lives when they’re truly needed, they’re often overprescribed and misunderstood.

Over time, dangerous bacteria can become resistant to antibiotics, making serious infections harder to fight. Before taking antibiotics or giving them to your children, talk to your doctor about alternative options and the unintended consequences to our microbiomes that can result from taking antibiotics too often and when they aren’t needed.

2. Lower Stress and Exercise More

Stress hinders immune function because your body diverts energy away from fighting off infections and places it on primary concerns that keep your alive — which is one reason why chronic stress can kill your quality of life. When your body thinks it’s facing an immediate danger, you become more susceptible to infections and experience more severe symptoms while also developing higher levels of inflammation.

Stress causes immune compounds known as cytokines to contribute to the inflammatory response that damages healthy cells. Exercise is a natural stress reliever that can help lower inflammation, balance hormones and strengthen the immune system.

3. Add Supplements

Co-enzyme Q10, carotenoids, omega-3 fish oil, selenium and antioxidants (vitamins C, D and E) can help keep free radical damage from disturbing micrbiota gut health.

Microbiome Issues

The microbiome is a lot like Earth’s ecosystems, meaning as its conditions change, so do the organisms that inhabit it. Microbes interact with one another within the community they live in (the gut), and they change in concentration depending on their surroundings — which means your diet, lifestyle, use of medications/antibiotics and environment really impact your gut health.

At the forefront of how your gut microbiome determines whether or not you’ll deal with various illnesses is inflammation.

Inflammation is the root of most diseases. Studies show that an anti-inflammatory lifestyle is protective over brain neurons, balances hormones, fights the formation of tumors and has mood-enhancing benefits.

While you might not think that gut health impacts your mood and energy much, think again. Gut-friendly bacteria can help manage neurotransmitter activity, which makes them natural antidepressants and anti-anxiety organisms.

Instead of taking anti-inflammatory medications to manage illnesses like arthritis or heart disease, we’re much better off reducing inflammation in the body.

Poor gut health is tied to dozens of diseases, especially:

- Autoimmune diseases (arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, Hashimoto’s disease, etc.). Autoimmune disorders develop when the body’s immune system goes awry and attacks its own healthy tissue. Inflammation and autoimmune reactions largely stem from an overactive immune system and poor gut health. Leaky gut syndromecan develop, which results in small openings in the gut lining opening up, releasing particles into the bloodstream and kicking off an autoimmune cascade.

- Brain disorders/cognitive decline (Alzheimer’s, dementia, etc.). Inflammation is highly correlated with cognitive decline, while an anti-inflammatory lifestyle has been shown to lead to better memory retention, longevity and brain health. We now know there are multiple neuro-chemical and neuro-metabolic pathways between the central nervous system/brain and microbiome/digestive tract that send signals to one another, affecting our memory, thought patterns and reasoning. Differences in our microbial communities might be one of the most important factors in determining if we deal with cognitive disorders in older age. A 2017 study by the University of Pennsylvania also found a relationship between the gut microbiome and the formation of cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs), which can cause stroke and seizures. Researchers observed that in mice, the activation of TLR4, a receptor for lipopolysaccharide (LPS) — a bacterial molecule — on brain endothelial cells by LPS greatly accelerated CCM formation. When mice were then observed in a germ-free environment, CCM formation greatly decreased, illustrating the effects of bad bacteria and the microbiome on cerebral cavernous malformations.

- Cancer. Many studies have shown a link between gut health and better protection from free radical damage, which causes brain, breast, colon, pancreatic, prostate and stomach cancers. Microbes influence our genes, which means they can either promote inflammation and tumor growth or raise immune function and act as potential natural cancer treatments. An anti-inflammatory lifestyle can also help lower serious side effects of cancer treatments (like chemotherapy).

- Fatigue and joint pain. Certain bacteria within our digestive tracts contribute to deterioration of joints and tissue. Research shows that a healthier gut environment helps lower the risk for joint pain, swelling and trouble moving in people with osteoarthritis and inflamed joints. Some studies have found that patients with psoriatic arthritis (a type of autoimmune joint disease) have significantly lower levels of certain types of intestinal bacteria and that patients with rheumatoid arthritis are more likely to have other strains present.

- Mood disorders (depression, anxiety). Ever hear of the “gut-brain connection”? Well here’s how it works: Your diet affects your microbiome and neurotransmitter activity, and therefore how you feel, your ability to handle stress and your energy levels. Dietary changes over the last century — including industrial farming, the use of pesticides and herbicides, and the degradation of nutrients in foods — are the primary forces behind growing mental health issues like depression. Low nutrient availability, inflammation and oxidative stress affect the neurotransmitters dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin, which control your moods, ease tension and raise alertness. It’s also a two-way street when it comes to your gut and mood: Poor gut health contributes to mood problems, and high amounts of stress also damage your gut and hormonal balance. A 2017 study illustrated the correlation between gut health and depression. Researchers studied 44 adults with irritable bowel syndrome and mild to moderate anxiety or depression. Half of the group took the probiotic Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001, and the other was given a placebo. Six weeks after taking probiotics daily, 64 percent of the patients taking the probiotic reported decreased depression. Of the patients taking a placebo, only 32 percent reported decreased depression.

- Learning disabilities (ADHD, autism). Our bodies are interconnected systems, and everything we put in them, expose them to or do to them affects the whole person, including growth, development and mental capabilities. ADHD and other learning disabilities have been tied to poor gut health, especially in infants and children. We are continuing to learn how our neurodevelopment, cognition, personality, mood, sleep and eating behaviors are all affected by the bacteria that reside within our guts. There seems to be an association between diet and psychiatric disorders due to metabolites of dietary components and enzymes encoded in the human genome that inhabit our guts. One of the most important factors seems to be establishing a healthy microbiome from birth, including a vaginal delivery ideally and being breastfed, which populates the newborn’s gut with the mother’s healthy bacteria.

- Infertility and pregnancy complications. We first start establishing our microbiomes at exactly the points we are born, and our environment continues to manipulate the bacteria within us for the remainder of our lives. As we age and change, so do our microbiota. This is both good and bad news. It means some of us might already be at a disadvantage if we were exposed to high amounts of bad bacteria or antibiotics at a young age, especially if we were also being withheld from good bacteria that we receive through being breastfed. At the same time, a healthy pregnancy, delivery and period of being breastfed can set the stage for a strong immune system.

- Allergies, asthma and sensitivities. Certain beneficial bacteria lower inflammation, which lessens the severity of allergic reactions, food allergies, asthma or infections of the respiratory tract. This means stronger defense against seasonal allergies or food allergies and more relief from coughing, colds, the flu or a sore throat. An anti-inflammatory diet helps prevent susceptibility to leaky gut syndrome and helps eliminate phlegm or mucus in the lungs or nasal passages, which makes it easier to breathe.

Related: Eat to Beat Disease: How to Eat for Optimal Health

Microbiome and Genes

Researchers often speak about the microbiota as the full collection of genes and microbes living within a community, in this case the community that inhabits our guts. According to the University of Utah Genetic Science Learning Center, “the human microbiome (all of our microbes’ genes) can be considered a counterpart to the human genome (all of our genes). The genes in our microbiome outnumber the genes in our genome by about 100 to 1.”

You might have learned in school when you were younger that all human beings actually have very closely related genetic codes, even though we are all so different-looking as a species. What’s amazing is that each of our gut microbiomes is vastly different. One of the most amazing things about the microbiome is how different it can be from one person to another.

Estimates of the human gene catalog show that we have about 22,000 “genes” (as we normally think of them) but a staggering 3.3 million “non-redundant genes” in the human gut microbiome! The diversity among the microbiome of individuals is phenomenal: Individual humans are about 99.9 percent identical to one another in terms of their host genomes but usually 80 percent to 90 percent different from one another in terms of the microbiomes.

Today, researchers are rapidly working on better understanding the microbiome in order to help prevent, cure or treat symptoms of all sorts of diseases that might stem back to the community living within each of us. DNA-sequencing tools are helping us uncover various bacterial strains and how they might hinder or help the immune system.

This effort is part of the Human Microbiome Project, done by the Data Analysis and Coordination Center for the National Institutes of Health. The goal is to “characterize microbial communities found at multiple human body sites and to look for correlations between changes in the microbiome and human health.”

While some bacteria contribute to diseases, many do not. In fact, there are lots of bacterial strains we could benefit from having more of.

At the same time, having certain diseases can negatively impact the microbiome, although we still have a lot to learn about how this happens exactly. The more we can come to understand how bacteria in the microbiome affect our genes and predispose us to diseases, the better we can personalize treatment approaches and prevent and manage diseases before they’re life-threatening.

Conclusion

- Microbiota are the trillions of bacterial organisms that live inside our bodies. The whole community of these bacteria is called the microbiome.

- Our gut is a central location of the microbiome, where the large majority of bacteria live.

- Poor gut health is tied to nearly every disease there is in some way, because this is where much of the immune system lives and where inflammation often begins.

- By improving your diet, eating plenty of anti-inflammatory foods and probiotics, lowering stress, and exercising regularly, you can support your body’s microbiome.